Articles For Farmers

This page is dedicated to educational articles for dairy and beef farmers all across the spectrum, from beginners to lifers. If you would like to suggest an article or write one to share, please e-mail me at [email protected] and include "farmer articles" in the subject line. Every attempt is made to make sure the information here is accurate and helpful. If you find a mistake, please send an e-mail!

Edema In First Calf Heifers

by Kassandre Moulton

Edema, which is swelling, often in the udder, due to fluid buildup, can be very painful to first calf heifers especially and can make them hard to handle. A heifer with edema is more likely to come back with edema during her next lactation. Heifers with edema are often slow to reach their desired production levels, losing money for the farmer. A mint based cream can often help the edema a little bit, but wouldn't you rather prevent edema from happening in the first place? Recent studies have shown that edema is greatly affected by pre-fresh nutrition.

Though it is not certtain what causes edema, many scientists think that sodium, potassium, and over conditioning play a role. One method is to eliminate free choice salts and buffers that have Na or K a few weeks before the heifer's due date. Following a good nutrition plan and managing the weight of pre-fresh heifers can work wonders, and may also prevent a host of other diseases, including ketosis.

Stress is also believed to be a factor in edema, as it is with many other health conditions. It is important for you, the producer, to manage stress in your animals. They should be comfortable at all times. Animals should be dealt with gently and calmly. If possible, reduce or eliminate loud noises near the animals.

Edema is just one of the things farmers must deal with when it comes to introducing first calf heifers to the milking herd. This disorder can wreak more havoc than many realize, but it is also very easy to manage if proper steps are taken.

Though it is not certtain what causes edema, many scientists think that sodium, potassium, and over conditioning play a role. One method is to eliminate free choice salts and buffers that have Na or K a few weeks before the heifer's due date. Following a good nutrition plan and managing the weight of pre-fresh heifers can work wonders, and may also prevent a host of other diseases, including ketosis.

Stress is also believed to be a factor in edema, as it is with many other health conditions. It is important for you, the producer, to manage stress in your animals. They should be comfortable at all times. Animals should be dealt with gently and calmly. If possible, reduce or eliminate loud noises near the animals.

Edema is just one of the things farmers must deal with when it comes to introducing first calf heifers to the milking herd. This disorder can wreak more havoc than many realize, but it is also very easy to manage if proper steps are taken.

Grass Tetany

by Kassandre Moulton

Grass Tetany is an often overlooked but dire condition that results from low magnesium levels in a cow’s bloodstream. It is a serious metabolic disease that primarily occurs in older cows nursing young calves. Symptoms of this disorder are an uncoordinated gait and convulsions, leading to coma and death. Grass Tetany most often occurs in cattle that are on pasture. Magnesium levels are often deplete in cool-season or winter annual grass pastures. Due to this, spring-calving cows are at a greater risk. Heavy milkers have an increased risk as well, since they have increased magnesium requirements. Unbalanced soil nutrients, such as nitrogen over-fertilization, can reduce magnesium availability in all types of pastures. Prevention seems to be relatively simple, by offering a high magnesium mineral mix. However, magnesium is not palatable, and even when in a mix, cows may not eat it. Careful monitoring is important, especially in herds with risk factors or a history of Grass Tetany. Adding legumes to the diet can add more natural magnesium. Routine soil tests can help farmers manage nutrients in order to maintain adequate magnesium levels.

Sources: The Progressive Farmer, Cattle Today

Sources: The Progressive Farmer, Cattle Today

Metabolic Disorders

by Kassandre Moulton

Calving and early lactation are important times in a cow’s life. Careful management before and during these periods can greatly reduce the occurrence of metabolic disorders, which can be fatal.

MILK FEVER

Contrary to what the name suggests, fever is not a symptom of milk fever. Cows with milk fever will lack an appetite, have cold ears, and be dull and listless. As the disorder progresses, the cow will be down and unresponsive. Her blood calcium levels will drop, and her digestive tract will be inactive. Milk fever is caused because the sudden and large volume of milk production causes an extra drain on the cow’s blood calcium and her metabolism isn’t able to respond in a timely manner. Treating milk fever begins with a slow IV of Calcium Gluconate. Additional IV’s may sometimes be given if necessary. There is a 30% chance that the cow will relapse after the initial recovery period that follows an IB. Milk fever prevention begins with the dry cow ration. Calcium should be fed as less than .5% of the dry matter in a ration, and phosphorous as less than .35%. Calcium gels can also be given to prefresh cows as a preventative.

KETOSIS

Ketosis is a disorder resulting from inadequate energy intake. When a cow’s blood glucose becomes low, she begins to mobilize her fat stores. The breakdown of these fats results in ketone production. These ketones begin to build up in the blood and liver, causing ketosis. Symptoms of ketosis include loss of appetite (especially for concentrates), a sweet smell to the cow’s breath, weight loss, rumen inactivity, and dull behavior. A test of the milk or urine can determine ketosis. To treat ketosis, a glucose IV can be given, but often has short lived effects. Hormonal treatments are another option, or oral sugar precursors can be fed or drenched to help the cow produce sugars in the liver. To prevent ketosis, avoid overconditioning and extreme dietary changes before and following calving. Feed high quality and palatable feeds to promote intake. A TMR can prevent sorting to encourage a balanced intake.

FAT COW SYNDROME (aka Fatty Liver Syndrome)

Fat Cow Syndrome has symptoms and causes similar to ketosis. A negative energy balance leads to fat mobilization and increased fats building up in the liver. As the name suggests, overconditioned cows often suffer from this disorder. Treatment is the same as ketosis. Prevention is simple-manage the body condition score (BCS) of late lactation and dry cows. Late lactation cows should have a BCS lower than 3.5 and dry cows lower than 4.0.

DISPLACED ABOMASUM (DA)

A DA usually occurs around calving. It is when the abomasum, or true stomach, twists to the side. 85% of the time it twists to the left and gets caught between the rumen and body wall. It is believed that a DA is caused by both metabolic and mechanical factors. Signs of a DA are depression, dehydration, an arched back, bloating, loss of appetite, and decreased manure production. A DA is often a secondary disorder to Fat Cow Syndrome, mastitis, or milk fever. Inadequate feed intake is another cause. Rolling is a popular treatment but is often not as effective as surgery. Prevention involves feeding cows properly as they transition from the dry stage into lactation. Bulky forages can help to keep the stomach full and in its proper place.

ACIDOSIS

Acidosis is a nutritional imbalance that causes low pH in the rumen. It is most often caused by a low fiber, high concentrate diet, or when a cow is allowed to overindulge (i.e. gets loose and gets into the grain bin). There is no good treatment for acidosis, so prevention is key. If concentrates are going to be added to a cow’s diet, it should be done gradually. Maintaining a good level of fiber in the diet is important, as is adequate intake. Buffers can be added to a ration to increase rumen pH as well.

LAMINITIS

Laminitis is a non-infectious inflammation of vascular tissue in the hood. Laminitis can vary in severity and duration. It may be caused by acidosis, histamine release, edema, or damaged capillaries. Hoof trimming can help control the laminitis in some cases, but for chronic cases, culling should be considered.

*This article is for informative purposes only. Please talk to your vet or nutritionist before taking treatment or preventative action.

Sources: McGill University, David Marcinkowski

MILK FEVER

Contrary to what the name suggests, fever is not a symptom of milk fever. Cows with milk fever will lack an appetite, have cold ears, and be dull and listless. As the disorder progresses, the cow will be down and unresponsive. Her blood calcium levels will drop, and her digestive tract will be inactive. Milk fever is caused because the sudden and large volume of milk production causes an extra drain on the cow’s blood calcium and her metabolism isn’t able to respond in a timely manner. Treating milk fever begins with a slow IV of Calcium Gluconate. Additional IV’s may sometimes be given if necessary. There is a 30% chance that the cow will relapse after the initial recovery period that follows an IB. Milk fever prevention begins with the dry cow ration. Calcium should be fed as less than .5% of the dry matter in a ration, and phosphorous as less than .35%. Calcium gels can also be given to prefresh cows as a preventative.

KETOSIS

Ketosis is a disorder resulting from inadequate energy intake. When a cow’s blood glucose becomes low, she begins to mobilize her fat stores. The breakdown of these fats results in ketone production. These ketones begin to build up in the blood and liver, causing ketosis. Symptoms of ketosis include loss of appetite (especially for concentrates), a sweet smell to the cow’s breath, weight loss, rumen inactivity, and dull behavior. A test of the milk or urine can determine ketosis. To treat ketosis, a glucose IV can be given, but often has short lived effects. Hormonal treatments are another option, or oral sugar precursors can be fed or drenched to help the cow produce sugars in the liver. To prevent ketosis, avoid overconditioning and extreme dietary changes before and following calving. Feed high quality and palatable feeds to promote intake. A TMR can prevent sorting to encourage a balanced intake.

FAT COW SYNDROME (aka Fatty Liver Syndrome)

Fat Cow Syndrome has symptoms and causes similar to ketosis. A negative energy balance leads to fat mobilization and increased fats building up in the liver. As the name suggests, overconditioned cows often suffer from this disorder. Treatment is the same as ketosis. Prevention is simple-manage the body condition score (BCS) of late lactation and dry cows. Late lactation cows should have a BCS lower than 3.5 and dry cows lower than 4.0.

DISPLACED ABOMASUM (DA)

A DA usually occurs around calving. It is when the abomasum, or true stomach, twists to the side. 85% of the time it twists to the left and gets caught between the rumen and body wall. It is believed that a DA is caused by both metabolic and mechanical factors. Signs of a DA are depression, dehydration, an arched back, bloating, loss of appetite, and decreased manure production. A DA is often a secondary disorder to Fat Cow Syndrome, mastitis, or milk fever. Inadequate feed intake is another cause. Rolling is a popular treatment but is often not as effective as surgery. Prevention involves feeding cows properly as they transition from the dry stage into lactation. Bulky forages can help to keep the stomach full and in its proper place.

ACIDOSIS

Acidosis is a nutritional imbalance that causes low pH in the rumen. It is most often caused by a low fiber, high concentrate diet, or when a cow is allowed to overindulge (i.e. gets loose and gets into the grain bin). There is no good treatment for acidosis, so prevention is key. If concentrates are going to be added to a cow’s diet, it should be done gradually. Maintaining a good level of fiber in the diet is important, as is adequate intake. Buffers can be added to a ration to increase rumen pH as well.

LAMINITIS

Laminitis is a non-infectious inflammation of vascular tissue in the hood. Laminitis can vary in severity and duration. It may be caused by acidosis, histamine release, edema, or damaged capillaries. Hoof trimming can help control the laminitis in some cases, but for chronic cases, culling should be considered.

*This article is for informative purposes only. Please talk to your vet or nutritionist before taking treatment or preventative action.

Sources: McGill University, David Marcinkowski

Reproductive Disorders in Cattle

by Kassandre Moulton

Reproductive disorders are bad news for cattle farmers. They can lead to longer calving intervals, delayed breeding, culling, and other health issues. The good news is that farmers can take steps to reduce and prevent the occurrence of many reproductive issues.

RETAINED PLACENTA (RP)

An RP occurs when the cow fails to fully expel the placenta within 12 hours after calving. The part of the placenta that has been expelled then acts as a wick, bringing bacteria into the reproductive tract. This leaves the cow susceptible to a cascade of other health problems. RP’s are a major cause of “problem breeders” (cows that require 3 + services). On average, about 10% of cows are affected by RPs. RP can be caused by many things, including:

-dystocia -twinning -abortion -infectious disease

-Calcium to Phosphorous imbalance -Selenium & Vitamin E definiciency -Fat Cow Syndrome

RPs can be treated. However, it is recommended that farmers do nothing as long as the cow is eating, not feverish, and not acting sick. However, if they cow is sick, systemic treatment with antibiotics may be affective. RPs may also be treated with a prostaglandin (Lutelyse) or oxytocin injections. If the cow is in very bad shape, it is a good idea to call the vet.

It is recommended that producers take direct action against RPs if you are seeing them in 20-25% of your herd. Preventative measures for RPs can include consulting with a nutritionist to prevent dry cow deficiencies, supplementations of Selenium and Vitamin E at dry off, avoiding fat cow syndrome by monitoring Body Condition Scores, and a comprehensive vaccination program to prevent abortion-causing diseases,

CYSTIC OVARIES

Cystic ovaries affect about 30% of cows in each lactation. About half can go unnoticed, so it is important to have your veterinarian check if you suspect cystic ovaries. There are two types of cystic ovaries: follicular, in which high levels of estrogen are produced, and luteal, in which high levels of progesterone are produced. These cysts can result in enlarged ovaries, “bulling”, and no signs of estrus or an erratic estrus cycle. The primary cause of this problem is an inadequate luteinizing hormone surge to release an egg from the ovary. Other causes include calving problems, milk fever, an RP, stress, genetics, high estrogen intake via feed, and over supplementation of Calcium. Ovarian cysts have a 50% spontaneous cure rate. Follicular cases can be treated with GnRH or HCG. Luteal cysts can be treated with prostaglandins. If you are in doubt as to what type of cysts a cow has, you can treat with both or do a milk progesterone test to determine the type. An ultrasound can also show what type of cyst is present. Cysts may be prevented with a low stress environment, balanced ration and the control of other postpartum diseases.

UTERINE INFECTION

Slight uterine infections are part of the normal postpartum uterine involution; however, sometimes these infections can get serious and affect the cow’s reproduction. There are different types of uterine infections to look out for:

Metritis: An infection of the uterine wall, glands, and muscle layers.

Endometritis: The endometrum (inside layer) and glandular tissue is infected.

Pyometra: A large accumulation of fluids and pus in the uterus.

All of these infections can be treated with lutelyse, sometimes in conjunction with oxytocin. You may also get some response using systemic antibiotics. Farmers can take steps to reduce uterine infections by offering a clean, dry, sanitized, and separate calving area. Frequent checks and balanced rations can help as well.

THE POSTPARTUM DISEASE COMPLEX

-A cow with milk fever is 4.2 times more likely to get dystocia, 1.6 times more likely to get metritis, and twice as likely to get an RP than a healthy cow.

-A cow with dystocia is 3.5 times as likely to get metritis and almost 4 times as likely to be culled from the herd.

-A cow with metritis is 1.7 times more likely to get cystic ovaries.

-A cow with an RP is 5.8 times more likely to get metritis and will likely have decreased reproductive efficiency.

-A cow with cystic ovaries is one and a half times as likely to be removed from the herd.

*Please note that the treatments mentioned above are only recommendations. Please check with your vet before taking an unfamiliartreatment action.

RETAINED PLACENTA (RP)

An RP occurs when the cow fails to fully expel the placenta within 12 hours after calving. The part of the placenta that has been expelled then acts as a wick, bringing bacteria into the reproductive tract. This leaves the cow susceptible to a cascade of other health problems. RP’s are a major cause of “problem breeders” (cows that require 3 + services). On average, about 10% of cows are affected by RPs. RP can be caused by many things, including:

-dystocia -twinning -abortion -infectious disease

-Calcium to Phosphorous imbalance -Selenium & Vitamin E definiciency -Fat Cow Syndrome

RPs can be treated. However, it is recommended that farmers do nothing as long as the cow is eating, not feverish, and not acting sick. However, if they cow is sick, systemic treatment with antibiotics may be affective. RPs may also be treated with a prostaglandin (Lutelyse) or oxytocin injections. If the cow is in very bad shape, it is a good idea to call the vet.

It is recommended that producers take direct action against RPs if you are seeing them in 20-25% of your herd. Preventative measures for RPs can include consulting with a nutritionist to prevent dry cow deficiencies, supplementations of Selenium and Vitamin E at dry off, avoiding fat cow syndrome by monitoring Body Condition Scores, and a comprehensive vaccination program to prevent abortion-causing diseases,

CYSTIC OVARIES

Cystic ovaries affect about 30% of cows in each lactation. About half can go unnoticed, so it is important to have your veterinarian check if you suspect cystic ovaries. There are two types of cystic ovaries: follicular, in which high levels of estrogen are produced, and luteal, in which high levels of progesterone are produced. These cysts can result in enlarged ovaries, “bulling”, and no signs of estrus or an erratic estrus cycle. The primary cause of this problem is an inadequate luteinizing hormone surge to release an egg from the ovary. Other causes include calving problems, milk fever, an RP, stress, genetics, high estrogen intake via feed, and over supplementation of Calcium. Ovarian cysts have a 50% spontaneous cure rate. Follicular cases can be treated with GnRH or HCG. Luteal cysts can be treated with prostaglandins. If you are in doubt as to what type of cysts a cow has, you can treat with both or do a milk progesterone test to determine the type. An ultrasound can also show what type of cyst is present. Cysts may be prevented with a low stress environment, balanced ration and the control of other postpartum diseases.

UTERINE INFECTION

Slight uterine infections are part of the normal postpartum uterine involution; however, sometimes these infections can get serious and affect the cow’s reproduction. There are different types of uterine infections to look out for:

Metritis: An infection of the uterine wall, glands, and muscle layers.

Endometritis: The endometrum (inside layer) and glandular tissue is infected.

Pyometra: A large accumulation of fluids and pus in the uterus.

All of these infections can be treated with lutelyse, sometimes in conjunction with oxytocin. You may also get some response using systemic antibiotics. Farmers can take steps to reduce uterine infections by offering a clean, dry, sanitized, and separate calving area. Frequent checks and balanced rations can help as well.

THE POSTPARTUM DISEASE COMPLEX

-A cow with milk fever is 4.2 times more likely to get dystocia, 1.6 times more likely to get metritis, and twice as likely to get an RP than a healthy cow.

-A cow with dystocia is 3.5 times as likely to get metritis and almost 4 times as likely to be culled from the herd.

-A cow with metritis is 1.7 times more likely to get cystic ovaries.

-A cow with an RP is 5.8 times more likely to get metritis and will likely have decreased reproductive efficiency.

-A cow with cystic ovaries is one and a half times as likely to be removed from the herd.

*Please note that the treatments mentioned above are only recommendations. Please check with your vet before taking an unfamiliartreatment action.

Genetic Defects of Cattle

by Kassandre Moulton

Increases in the use of artificial insemination, and in turn the narrowing of the bovine gene pool in recent decades has led to the surfacing and accumulation of genetic defects. Many producers are not fully aware of educated about these defects until one of them hits their herd. By knowing how these defects can affect your herd, and where they originate, you can reduce their occurrence to protect your bottom line.

BLAD-Bovine Leukocyte Adhesion Deficiency

BLAD is a defect of Holsteins, originating in descendents of Osborndale Ivanhoe. Notable carriers include Penstate Ivanhoe Star and Carlin-M Ivanhoe Bell. This disease was first identified in the early 1980’s and is an autosomal recessive hereditary disease. Carriers may seem completely normal but have a 25% chance of having offspring with the disease. Calves infected with BLAD will have poor health and usually die around 2-4 months of age. Animals that survive often suffer from stunted growth and reoccurring infections. BLAD status can be determined by using a PCR (Polymerase Chain Reaction) DNA test. At one point, 15% of bulls and 8% of cows in the breed were carriers.

DUMPS-Deficiency of Uridine Monophosphate Synthetase

DUMPS is a deficiency of an essential enzyme that is found in all body cells. This deficiency is due to a point mutation in the DNA that codes for the enzyme. It is an embryonic lethal, meaning that the fetus of an unborn calf will die at about day 40. Major carriers of this defect are Happy Herd Beautician and Skokie Sensation Ned.

AM/Curly Calf-Arthrogryposis Multiplex

Curly Calf is a defect of the Angus breed. About 25% of calves born to carrier parents will be born dead or die shortly after birth. However, there is a 50% chance that the offspring will survive to become another carrier. If a carrier is mated to a non-carrier, the syndrome will not be expressed, but has a 50% chance of producing a carrier. The spine and legs of these dead calves will appear twisted and limbs may be contracted. The calves will have an overall thin appearance. This is a relatively new defect first noticed by producers in early 2007.

CVM-Complex Vertebral Malformation

CVM is a defect of Holsteins. Calves will have a shortened neck and contracted limb joints. The defect can be lethal or result in abortion. Many affected calves have heart malformations as well.

Weaver- Bovine Progressive Degenerative Myelo-encephalopathyWeaver is a Brown Swiss defect, given its common name due to the weaving gait of affected animals. This defect attacks the brain and spinal cord. Symptoms include lack of coordination, slight swaying when standing, hind feet close together or crossing, leaning, and loss of control. Symptoms are generally noticeable between 6-18 months of age. The animal usually doesn’t die until 2-3 years of age, but will eventually suffer from malnutrition and muscle atrophy in addition to the original symptoms. The Brown Swiss Association recommends keeping the animal off concrete or other hard surfaces to prevent injury, and to have your veterinarian euthanize the animal when it can no longer eat or drink.

TH-Tibial HemimeliaTH is a Shorthorn defect first detected in 1999. TH infected calves will be born with twisted legs and fused joints, and/or abdominal hernias and misshapen skulls. Many are born dead, but if they are born alive will need to be euthanized because it will not be able to stand or nurse. Deerpark Improver, a bull imported to the U.S. in the 70’s, is believed to have been the origination of the defect.

Mulefoot-Syndactyly

Mulefoot affects several breeds of cattle. It is mostly a cosmetic defect, resulting in an animal having only one toe rather than the usual two. It normally affects the front feet, but can affect the rear ones as well.

Marble Bone Disease-Osteopetrosis

Osteopetrosis has been found in several breeds. Calves will be born dead and often premature. The body may be unusually small and the lower jaw may be undershot. Bones will be solid and thick but lacking a bone marrow cavity.

Limber Leg

Limber Leg is a defect of the Jersey breed, controlled by a recessive gene. Some calves will be born dead; survivors will appear normal but be unable to stand. Muscles, tendons, ligaments, and joints will be malformed or underdeveloped. The shoulder and hip joints will be able to be rotated without any apparent discomfort to the calf.

RVC-Recto-Vaginal Constriction

RVC affects Jersey cattle of both sexes. In females it results in the compression of the genital tract and the sphincter or both sexes. Dystocia, udder edema, and excess fibrous tissue on the genital/rectal muscles often accompany this defect.

Sources: David Marcinkowski, Amy Brent, American Angus Association, Cattle Network, Jorgen S. Agerholm et al, Brown Swiss Association, John Hendrickson, Merck Veterinary Manual

BLAD-Bovine Leukocyte Adhesion Deficiency

BLAD is a defect of Holsteins, originating in descendents of Osborndale Ivanhoe. Notable carriers include Penstate Ivanhoe Star and Carlin-M Ivanhoe Bell. This disease was first identified in the early 1980’s and is an autosomal recessive hereditary disease. Carriers may seem completely normal but have a 25% chance of having offspring with the disease. Calves infected with BLAD will have poor health and usually die around 2-4 months of age. Animals that survive often suffer from stunted growth and reoccurring infections. BLAD status can be determined by using a PCR (Polymerase Chain Reaction) DNA test. At one point, 15% of bulls and 8% of cows in the breed were carriers.

DUMPS-Deficiency of Uridine Monophosphate Synthetase

DUMPS is a deficiency of an essential enzyme that is found in all body cells. This deficiency is due to a point mutation in the DNA that codes for the enzyme. It is an embryonic lethal, meaning that the fetus of an unborn calf will die at about day 40. Major carriers of this defect are Happy Herd Beautician and Skokie Sensation Ned.

AM/Curly Calf-Arthrogryposis Multiplex

Curly Calf is a defect of the Angus breed. About 25% of calves born to carrier parents will be born dead or die shortly after birth. However, there is a 50% chance that the offspring will survive to become another carrier. If a carrier is mated to a non-carrier, the syndrome will not be expressed, but has a 50% chance of producing a carrier. The spine and legs of these dead calves will appear twisted and limbs may be contracted. The calves will have an overall thin appearance. This is a relatively new defect first noticed by producers in early 2007.

CVM-Complex Vertebral Malformation

CVM is a defect of Holsteins. Calves will have a shortened neck and contracted limb joints. The defect can be lethal or result in abortion. Many affected calves have heart malformations as well.

Weaver- Bovine Progressive Degenerative Myelo-encephalopathyWeaver is a Brown Swiss defect, given its common name due to the weaving gait of affected animals. This defect attacks the brain and spinal cord. Symptoms include lack of coordination, slight swaying when standing, hind feet close together or crossing, leaning, and loss of control. Symptoms are generally noticeable between 6-18 months of age. The animal usually doesn’t die until 2-3 years of age, but will eventually suffer from malnutrition and muscle atrophy in addition to the original symptoms. The Brown Swiss Association recommends keeping the animal off concrete or other hard surfaces to prevent injury, and to have your veterinarian euthanize the animal when it can no longer eat or drink.

TH-Tibial HemimeliaTH is a Shorthorn defect first detected in 1999. TH infected calves will be born with twisted legs and fused joints, and/or abdominal hernias and misshapen skulls. Many are born dead, but if they are born alive will need to be euthanized because it will not be able to stand or nurse. Deerpark Improver, a bull imported to the U.S. in the 70’s, is believed to have been the origination of the defect.

Mulefoot-Syndactyly

Mulefoot affects several breeds of cattle. It is mostly a cosmetic defect, resulting in an animal having only one toe rather than the usual two. It normally affects the front feet, but can affect the rear ones as well.

Marble Bone Disease-Osteopetrosis

Osteopetrosis has been found in several breeds. Calves will be born dead and often premature. The body may be unusually small and the lower jaw may be undershot. Bones will be solid and thick but lacking a bone marrow cavity.

Limber Leg

Limber Leg is a defect of the Jersey breed, controlled by a recessive gene. Some calves will be born dead; survivors will appear normal but be unable to stand. Muscles, tendons, ligaments, and joints will be malformed or underdeveloped. The shoulder and hip joints will be able to be rotated without any apparent discomfort to the calf.

RVC-Recto-Vaginal Constriction

RVC affects Jersey cattle of both sexes. In females it results in the compression of the genital tract and the sphincter or both sexes. Dystocia, udder edema, and excess fibrous tissue on the genital/rectal muscles often accompany this defect.

Sources: David Marcinkowski, Amy Brent, American Angus Association, Cattle Network, Jorgen S. Agerholm et al, Brown Swiss Association, John Hendrickson, Merck Veterinary Manual

Effects of Increased Milking Frequency on Production

by Kassandre Moulton

Most farms milk their cows on a twice a day schedule. However, some have increased their frequency to three times a day in order to get increased production. But is the switch (increased labor, increased feed, etc.) really worth it? According to a lecture by David Marcinkowski, extension dairy specialist at the University of Maine, there are some changes in production with increased milkings:

Frequency Increase in production

From 1x to 2x 13.6 lb

From 2x to 3x 7.7 lb

From 2x to 4x 10.8 lb

Younger animals typically respond better than older ones. Timing also has an impact on the results of increased milking. If increased frequency is initiated mid-lactation, production will increase for a short period, then slowly decline to the pre-increase level. The best time to introduce an increased frequency is at the beginning of a lactation. Cows on an increased frequency schedule are also less likely to get mastitis because there is less pressure buildup in the udder. Still, before increasing frequency, it is important to compare the costs of increased feed and labor to the benefits of milking more than twice a day.

Frequency Increase in production

From 1x to 2x 13.6 lb

From 2x to 3x 7.7 lb

From 2x to 4x 10.8 lb

Younger animals typically respond better than older ones. Timing also has an impact on the results of increased milking. If increased frequency is initiated mid-lactation, production will increase for a short period, then slowly decline to the pre-increase level. The best time to introduce an increased frequency is at the beginning of a lactation. Cows on an increased frequency schedule are also less likely to get mastitis because there is less pressure buildup in the udder. Still, before increasing frequency, it is important to compare the costs of increased feed and labor to the benefits of milking more than twice a day.

Mastitis Organisms

by Kassandre Moulton

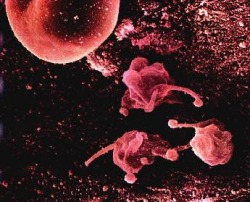

Mycoplasma organism

Any dairy farmer is familiar with mastitis. Mastitis is an inflammation of milk secreting tissues due to a microbial infection. This disease costs dairy farmers over two billion dollars annually. It can result in decreased production, culling and death loss, and loss of premiums. Mastitis may be clinical, in which the mastitis is visible in the form of inflammation. These cases, however, are usually just the tip of the iceberg. Subclinical mastitis can be detected by observing for an increase in Somatic Cell Count, or SCC (an SCC of >240,000 is considered infected) and a variety of lab tests. Mastitis can be caused by contagious organisms or environmental ones. The number one cause of mastitis in the U.S. is staph aureus, but there are many others that cause problems.

Organism Source Type Notes

Strep Ag. Infected cows or personnel Contagious Can be treated with penicillin

Staph Aureus Personnel, milking machine Contagious Difficult to eliminate; resists phagocytosis

Mycoplasma contaminated syringes Contagious Antibiotics ineffective, tan/sandy milk

& equipment

E.Coli Wet milking, coliforms Environmental Subnormal body temperature, watery milk.

in environment

Klebsiella Soil contamination, often Environmental Similar to e.coli symptoms.

in bedding

Strep NonAg. Environment, poor Environmental swelling, clots and flakes in udder/milk

sanitation

Coagulase Environment, poor Environmental High spontaneous cure rate, may prevent other

Negative sanitation forms of mastitis. Common in well-managed

Staph herds

Some cases of mastitis are treatable with antibiotics, but prevention is the best way to control mastitis in your herd. Routine testing and examination or DHIA records, proper sanitation of equipment, using dry bedding, milking infected cows last, and taking biosecurity measures can go a long ways in managing mastitis.

Organism Source Type Notes

Strep Ag. Infected cows or personnel Contagious Can be treated with penicillin

Staph Aureus Personnel, milking machine Contagious Difficult to eliminate; resists phagocytosis

Mycoplasma contaminated syringes Contagious Antibiotics ineffective, tan/sandy milk

& equipment

E.Coli Wet milking, coliforms Environmental Subnormal body temperature, watery milk.

in environment

Klebsiella Soil contamination, often Environmental Similar to e.coli symptoms.

in bedding

Strep NonAg. Environment, poor Environmental swelling, clots and flakes in udder/milk

sanitation

Coagulase Environment, poor Environmental High spontaneous cure rate, may prevent other

Negative sanitation forms of mastitis. Common in well-managed

Staph herds

Some cases of mastitis are treatable with antibiotics, but prevention is the best way to control mastitis in your herd. Routine testing and examination or DHIA records, proper sanitation of equipment, using dry bedding, milking infected cows last, and taking biosecurity measures can go a long ways in managing mastitis.

Effective Record Keeping & Farm Office Management

by Kassandre Moulton

Record keeping and office work is one aspect of running a farm that many people overlook or fall behind in. This is unfortunate, as record keeping can help farmers organize information, manage money, recognize problems early, and be better businessmen and women as a result. There are several aspects to farm office organization, including money management, herd records, and business transaction documentation. While it may seem like an ominous task to start or re-organize your farm record keeping, it will benefit your business in the long run.

Keeping monetary records is essential to anyone who is self-employed at any scale. Maintaining a record of purchases, sales, and other business deals allows for quick access if there is a question regarding a transaction. It enables a producer to quickly asses how much they owe and what the overall current money situation is for the farm. Detailed and easily accessible financial records certainly come in handy at tax time or when debating a big-ticket purchase. A filing cabinet with folders for different categories can allow you to keep receipts, invoices, and bills of sale close at hand. You can organize them in order according to date for quick location. Folders can be categorized in whatever way is convenient for you, such as one for each piece of farm equipment, or one for each year of feed sales. A computer program such as Microsoft Money can make records understandable and easy to access, but it is often a good idea to keep a hard copy of this information, or several backups on a thumb drive or CD in case of a computer crash or virus.

Herd records can also be kept on a computer. Programs such as PCDart or CattleMax allow a variety of information to be inputted, on both individual animals and the entire herd. Computer records are easy to search and can be printed on demand. However, many farmers find it inefficient to have to boot up the computer and program for every piece of data they need to input (i.e. an injury, newborn calf, breeding, etc.). One solution is to keep handwritten notes then input them at the end of each day or week. A variety of information can be kept on a herd of cattle, and what you choose to record can depend on what sort of operation you manage (i.e. a producer of registered heifers needs to have pedigree information for buyers while this sort of information is not as important to someone raising feeder calves).

Keeping track of this type of information allows you to know your animals well and be able to find what you need quickly. Keeping track of individual information can allow you to more efficiently manage your herd-you will know when heifers are ready to be bred or which of your cows is lacking in production. You can use your own records in conjunction with EPD’s from your breed association or DHIA results. Potential buyers will be impressed and more eager to make purchases when you give them full disclosure about an animal and can provide them with detailed records.

Organized and detailed record keeping allows you to be successful in your business. You will have essential information at your fingertips. It will be hard for anyone to dispute you if your records are kept properly. It does require some extra work, but record management will allow your business to flourish in other areas as well.

Supplies You May Need:

-computer -backup thumb drive or CD’s -filing cabinet -writing utensils

-notebooks -ledger (for hard copies) -printer -binder (for holding notes, registration papers, breeding slips, etc.) -folders

Information You May Want To Consider Keeping On Your Cattle:

-individual name or identification -sire & dam -registration numbers of individual and parents -breeding records -medical records -tag & tattoo information

-birth weights, weaning weights, etc. -hip heights and frame scores

-castration, dehorning, etc. dates -vaccination records -travel records (to fairs, etc.)

-body condition scores -production records -calving records/offspring

-other relevant notes

Keeping monetary records is essential to anyone who is self-employed at any scale. Maintaining a record of purchases, sales, and other business deals allows for quick access if there is a question regarding a transaction. It enables a producer to quickly asses how much they owe and what the overall current money situation is for the farm. Detailed and easily accessible financial records certainly come in handy at tax time or when debating a big-ticket purchase. A filing cabinet with folders for different categories can allow you to keep receipts, invoices, and bills of sale close at hand. You can organize them in order according to date for quick location. Folders can be categorized in whatever way is convenient for you, such as one for each piece of farm equipment, or one for each year of feed sales. A computer program such as Microsoft Money can make records understandable and easy to access, but it is often a good idea to keep a hard copy of this information, or several backups on a thumb drive or CD in case of a computer crash or virus.

Herd records can also be kept on a computer. Programs such as PCDart or CattleMax allow a variety of information to be inputted, on both individual animals and the entire herd. Computer records are easy to search and can be printed on demand. However, many farmers find it inefficient to have to boot up the computer and program for every piece of data they need to input (i.e. an injury, newborn calf, breeding, etc.). One solution is to keep handwritten notes then input them at the end of each day or week. A variety of information can be kept on a herd of cattle, and what you choose to record can depend on what sort of operation you manage (i.e. a producer of registered heifers needs to have pedigree information for buyers while this sort of information is not as important to someone raising feeder calves).

Keeping track of this type of information allows you to know your animals well and be able to find what you need quickly. Keeping track of individual information can allow you to more efficiently manage your herd-you will know when heifers are ready to be bred or which of your cows is lacking in production. You can use your own records in conjunction with EPD’s from your breed association or DHIA results. Potential buyers will be impressed and more eager to make purchases when you give them full disclosure about an animal and can provide them with detailed records.

Organized and detailed record keeping allows you to be successful in your business. You will have essential information at your fingertips. It will be hard for anyone to dispute you if your records are kept properly. It does require some extra work, but record management will allow your business to flourish in other areas as well.

Supplies You May Need:

-computer -backup thumb drive or CD’s -filing cabinet -writing utensils

-notebooks -ledger (for hard copies) -printer -binder (for holding notes, registration papers, breeding slips, etc.) -folders

Information You May Want To Consider Keeping On Your Cattle:

-individual name or identification -sire & dam -registration numbers of individual and parents -breeding records -medical records -tag & tattoo information

-birth weights, weaning weights, etc. -hip heights and frame scores

-castration, dehorning, etc. dates -vaccination records -travel records (to fairs, etc.)

-body condition scores -production records -calving records/offspring

-other relevant notes